Green Giants

Ancient mariners defy industrial chaos and urban sprawl

Even most locals in Chula Vista, California, the second-to-last city you pass through before crossing the Mexican border into Tijuana, are unaware of what lies beneath San Diego Bay. A colony of sixty to a hundred sea turtles has somehow thrived, virtually undetected, in one of the busiest, most developed natural harbors in teh world. These particular Eastern Pacific green turtles are super-sized, some weighing more than 550 pounds-almost double the average size of the same species in other habitats.

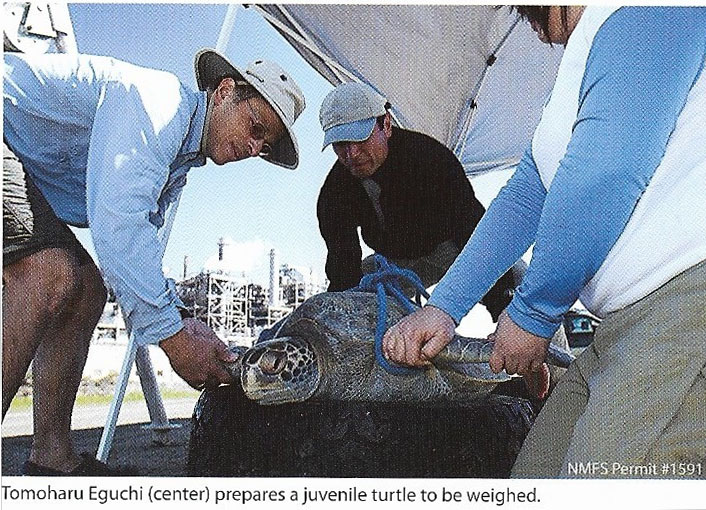

"They're monsters, I tell ya," says Jeffrey Seminoff, ecologist and assistant team leader for the Marine Turtle Research Group, part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) Southwest Fisheries Science Center. Seminoff is wearing orange coveralls and flip-flops, standing at the Boston Whaler's pedestal helm as we glide over the dusky water in late morning. Twice a month, he and a team of researchers use two 17-foot Whalers to make sweeps of South Bay, netting green turtles and hauling them back to shore to be weighed, tagged, and sampled before being released as part of a pathbreaking new study.

There are four of us crammed in the little boat, one of whom is NOAA Fisheries ecologist Tomoharu Eguchi. He's the man with all the stats, such as the fact that some of these enigmatic turtles are growing 8 to 10 centimetres a year. "That's quadruple the rate of green turtles at other sites," he shouts over the noise of the outboard motor. In comparison, genetically similar green turtles in the Sea of Cortez grow only about two centimeters a year, and rarely top 300 pounds.

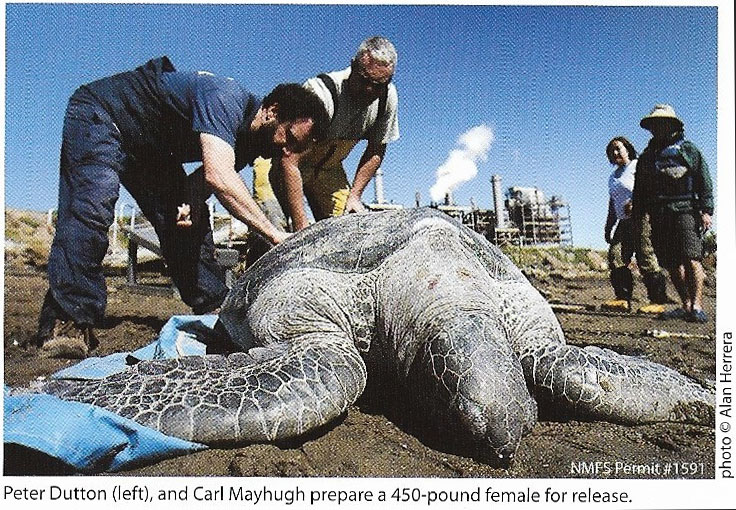

There is extreme tidal flux in South Bay. The water is low this morning, exposing unique habitat of intertidal and salt marshes, a refuge for wintering birds such as surf scter, scaup, brant, and bufflehead. Hidden in the murky waters, green turtles take sanctuary among the eelgrass beds. The one we're going after is just ahead. It struggles in the buyoed net, flippers windmilling and splashing as its head breaches for air. It's a 350-pound female, too large to be lifted onto the boat without reinforcements. Pretty soon the other Boston Whaler, helmed by Carl Mayhugh, arrives with the additional muscle needed to haul her out. Mayhugh is a Prescott College graduate student writing his master's thesis on the movements and habitat use of these turtles. This giantess is so burdensome that the boat's starboard gunwale dips underwater as three men grunt her aboard.

It's a good day for catching turtles.

Back ashore, there's already a 139-pound juvenile and a whopping 450-pound female being processed at the makeshift lab camp, a tent canopy pitched on a land spit that juts out below the hulking South Bay Power Plant. The steam electric power-generating facility, built in 1956, is one of the primary reasons turtles are so active here. It uses what's called a "once-through wet-cooling system" that draws seawater from the bay. The cooling water is heated after recondensing the steam that goes through the turbine generators, then flushed back out to sea, warming its discharge channel in South Bay up to 15 degrees above normal temperature.

The turtles are attracted to and affected by this warm-water effluent, especially during the winter. The higher water temperature decreases the amount of oxygen in the water and, in turn, increases the turtles' metabolic rate. Mayhugh theorizes that they may be growing so large because the warmer water allows them to continue foraging in winter, a time when green turtles in the Sea of Cortez "bury themselves down in the mud and go into a state of torpor for a few months," he says. "But here, they're active year round. They're eating all the time"

Seminoff isn't ready to corroborate this theory, since there have been studies of sea turtle populations in other power plant-warmed waters with no unusual size differential. But both researchers suspect that the turtles' usual herbivorous diet of eelgrass and algae is being supplemented with animal matter; turtles in teh Sea of Cortez have been observed feeding on tube worms, sea hares, jellyfish, and other slow-moving, soft-bodied sea creatures. Seminoff is using a revolutionary technology called "stable isotope analysis" to determine the South Bay turtle's diet.

Under the lab camp tent canopy, the 450-pound female's plastron rests on an old truck tire so that her flippers cannot touch the ground and allow her to escape. A wet rag covers her face to keep her calm. Her silent dignity is majestic, as Seminoff squats next to her head and, with the delicacy of a neurosurgeon, takes a dime-sized skin sample from her neck. A stable isotope analysis of it will determine if the turtle is a pure vegetarian or eats some mean. The technology could also be used on humans. "If you ate salad for the last week, then shaved, and I analyzed your whiskers, I could tell you your diet was all vegetarian that week, or if you had meat or chicken," says Seminoff. "It's a really novel technique that's just now being developed for wildlife."

A small sonic transmitter is attached to each turtle's shell using epoxy. Mayhugh has placed an array of underwater receiving stations around the Bay. As a turtle swims by, its identifying transmitter signal is picked up by the receiver, which records the date and time. "It's important to understand the movements and habitat use of the turtles so that a management plan for their protection can be developed," says Mayhugh.

The turtles are also given a health assessment, based on blood and tiny shell samples, that determines the amount of trace metals and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) in their systems. This toxicological study is important, since San Diego Bay is laden with contaminants and heavy metals from boats, the power plant, and urban runoff. "We want to see to what extent those metals and contaminants bioaccumulate in the turtles and how it affects their health," Seminoff explains. So far, the turtles seem to be weathering the industrial contaminants without adverse health effects, but the jury is still out on the hazards of long-term exposure.

South Bay represents the northernmost site on the continental West Coast where green turtles live year-round. The mystery of their origin inspires urban folklore. One rumor is that the turtles are not a natural aggregation, but the offspring of escapees from a supposed turtle cannery that operated along San Diego Bay at the turn of the century. "That's hogwash," says Seminoff. "This is absolutely a natural population. Every year we have new animals coming in-we call them 'new recruits'-and it really suggests to us that it's a vibrant population constantly being recharged with new younger animals."

New recruits are as small as 15 pounds. Once they come into the habitat, they will stay until they reach sexual maturity, somewhere between ten to twenty-five years. Then they are compelled to return to their natal beach to reproduce and lay eggs. "Breeding happens offshore of their natal beach," explains Peter Dutton, as he pours cool water over the 350-pound female's carapace to keep her from overheating in the sun. Dutton is team leader of the Marine Turtle Research Group. "During mating, four or five males will try and mount one female. It's brutal. The female will eventually lay three to six clutches of eggs, one clutch about every fifteen days, until all her eggs are gone."

Larger adult females are fitted with an Argos satellite tag. Tagged South Bay turtles have been tracked over 1,000 kilometers south to the Revillagigedos Islands, the Tres Marias Islands, and other remote areas south of the border. Seminoff says, "They're a transboundary species. They don't pay attention to any national borders, so we're doing our best to work with our counterparts in the Mexican government to ensure the turtles have some level of protection that's ongoing. The neat thing is that after they nest, they come back up into San Diego Bay. So they come back home basically."

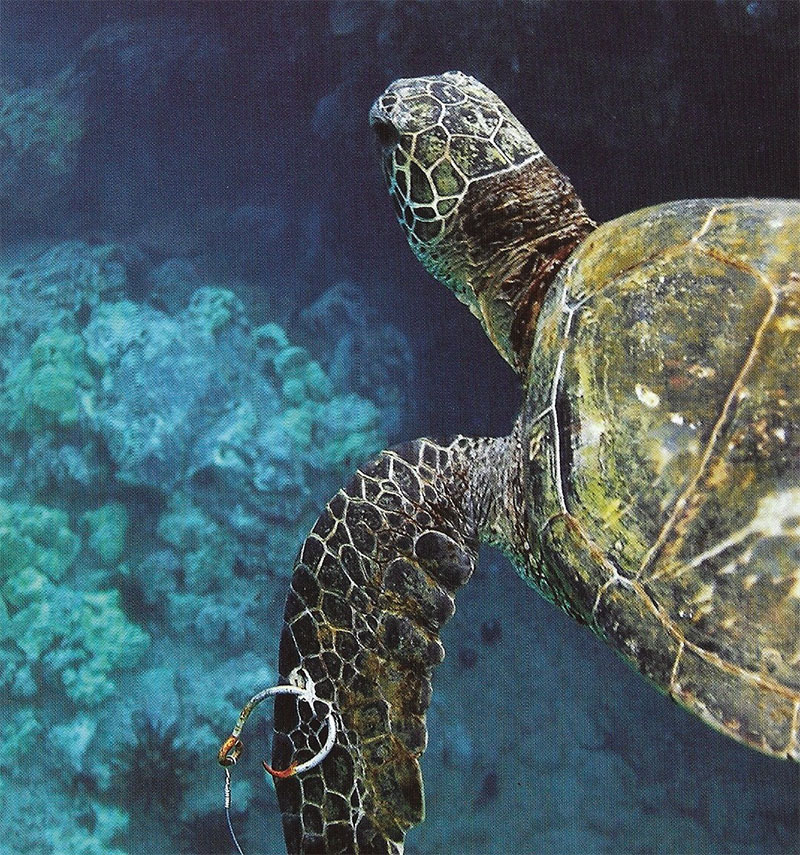

Transboundary protection is crucial. During their migration south, the turtles come into serious peril. Poachers still hunt them throughout Mexico, even though all five species of Eastern Pacific sea turtles-hawksbills, loggerheads, leatherbacks, olive ridleys, and greens-are endangered and protected by international law. Every year, about 35,000 turtles are captured in Baja waters alone, butchered for consumption locally or trafficked north to buyers in Ensenada and Tijuana who pay about $500 per turtle. In addition, sea turtles risk entanglement as incidental bycatch in fishing nets and longline gear. Thousands drown in this way each year; their carcasses are tossed back into the sea and wash up on Baja beaches with unceasing regularity.

Meanwhile, the South Bay Power Plant has outlived its usefulness, currently operating at only one-third capacity. It's slated to be closed and torn down in the next several years. But the resident green turtles will likely remain in South Bay even after their warm-water oasis cools. They've found safe haven here.

"They're incredibly resilient," says Seminoff. "As long as you don't hunt them or eat them or steal their eggs, they can deal with cities, habitats, a little coastal development, and not the best water conditions. I think they demonstrate that green turtles and humans can live harmoniously"

Client

WETPIXEL Quarterly

Date

Issue 3, 2008