Real Men Don't Eat Turtle Eggs

To Fight Turtle Poaching, Campaigners Hit Below the Belt

In Mexico's Magdalena Bay in Baja California, A Trans Am pulls into a village courtyard, parking behind an underground restaurant. When the trunk is opened, it's full of green turtles flipped on their backs, alive and kicking. Jeffrey Brown, an American photojournalist, starts taking pictures Alongside him is J. Wallace Nichols, biologist with the Californai Academy of Sciences who, in 1998, co-founded Groupo Tortuguero ("Turtle Group") in hopes of recovering the five endangered species of Eastern Pacific Sea Turtles- hawksbills, loggerheads, leatherbacks, olive ridleys and green turtles- that forage and nest along Baja peninsula. The two have negotiated their way into this "speakeasy" underworld.

A notorious poacher known only as "Lobo" takes the reptiles from teh trunk. "He proceeded to lay the turtles out and hit each one over the head with a two-by-four then butchered them up." recalls Brown, who kept the camera snapping to document the continued poaching and over-consumption of sea turtles in Mexico. After the slaughter "the old grandma" in the restaurant kitchen made turtle soup for waiting customers.

This practice remains "business as usual" in such makeshift restaurants throughout Baja, even though sea turtle hunting and consumption has been banned since 1990.

"I don't see too many turtles anymore," says Alvaro Romero, a 78-year-old fisherman who has lived in Loreto all his life. He stopped fishing for turtles long ago because he didn't want to see them disappear. "Always kill, kill, killing of the turtles," says Romero who nowadays gives eco-tours of Coronado Island on his small boat, known as a panga. He says that poachers hunt turtles at night around neighboring Carmen Island. They hunt underwater with flashlights, using a hookah or free diving. A swimming turtle is grabbed by the top edge of its shell and forced to surface where another pacher, waiting in a panga, pulls it aboard by its flippers. The animals can weigh over 200 pounds. The turtles are butchered for consumption locally or trafficked north, fresh, for buyers in Ensenada and Tijuana who pay about $500 per turtle.

In Baja alone, an estimated 35,000 turtles die in the hands of pachers annually, speared, harvested with long gillnets or caught by hand. Four species of marine turtles are already ecologically extince.

Across the Sea of Cortez along the mainland coastline, turtle eggs are in high demand. The olive ridley population along Oaxaca's 310-mile coastline is one of the most productive in the world and a main source of egg poaching. In the mid 1990's, egg snatchers converged along two main beaches near the city of Juchitan during arribada (mass turtle netings), blatantly picking the area clean with no intervention from law enforcement. Lately, police or soldiers guard arribada events. But poachers use bribery or raid unprotected nesting sites, selling the eggs to commercial traffickers.

"It's making all these egg traffickers very rich," says an ex-official for the Environmental Law Enforcement Agency (aka PROFEPA) in the Oaxaca region, who asked for anonymity. "Because they buy something like 100 eggs off the beach for about four pesos (36 cents) then they sell you three eggs in the marketplace for 10 pesos (90 cents). So the profit is enormous. And there's plenty to spread around to pay off the police and whoever else."

Commercial traffickers use underage girls to smuggle eggs across the main highway between Oaxaca and Juchitan in buses or pickup trucks jammed with passengers. PROFEPA inspectors regularly intercept two or three sacks of eggs in the luggage compartments of buses at police-supported checkpoints. But the female mules, averaging 15 or 16 years old, are virtually untouchable, "trained" to cry rape or sexual abuse if the police dare take them into custody. Most policemen want to avoid the complications of such charges.

Turtle poachers in Baja are often paid with drugs, traveling the same backroads as narco-traffickers, using walkie-talkies or bribery to negotiate military checkpoints. In Oaxaca, taxi drivers are on-the-take as lookouts, because they have car radios and can warn smuggler trucks-carrying anywhere between 5,000 to 100,000 eggs to commercial centers like Acapulco, Guerrero and Mexico City-about surprise checkpoints.

Turtle smuggling is thought to be a proving ground, a gateway into drug trafficking. Mexico is the principal transit country for 70 to 90 percent of cocaine entering the U.S., and the largest outside source of marijuana and methamphetamine.

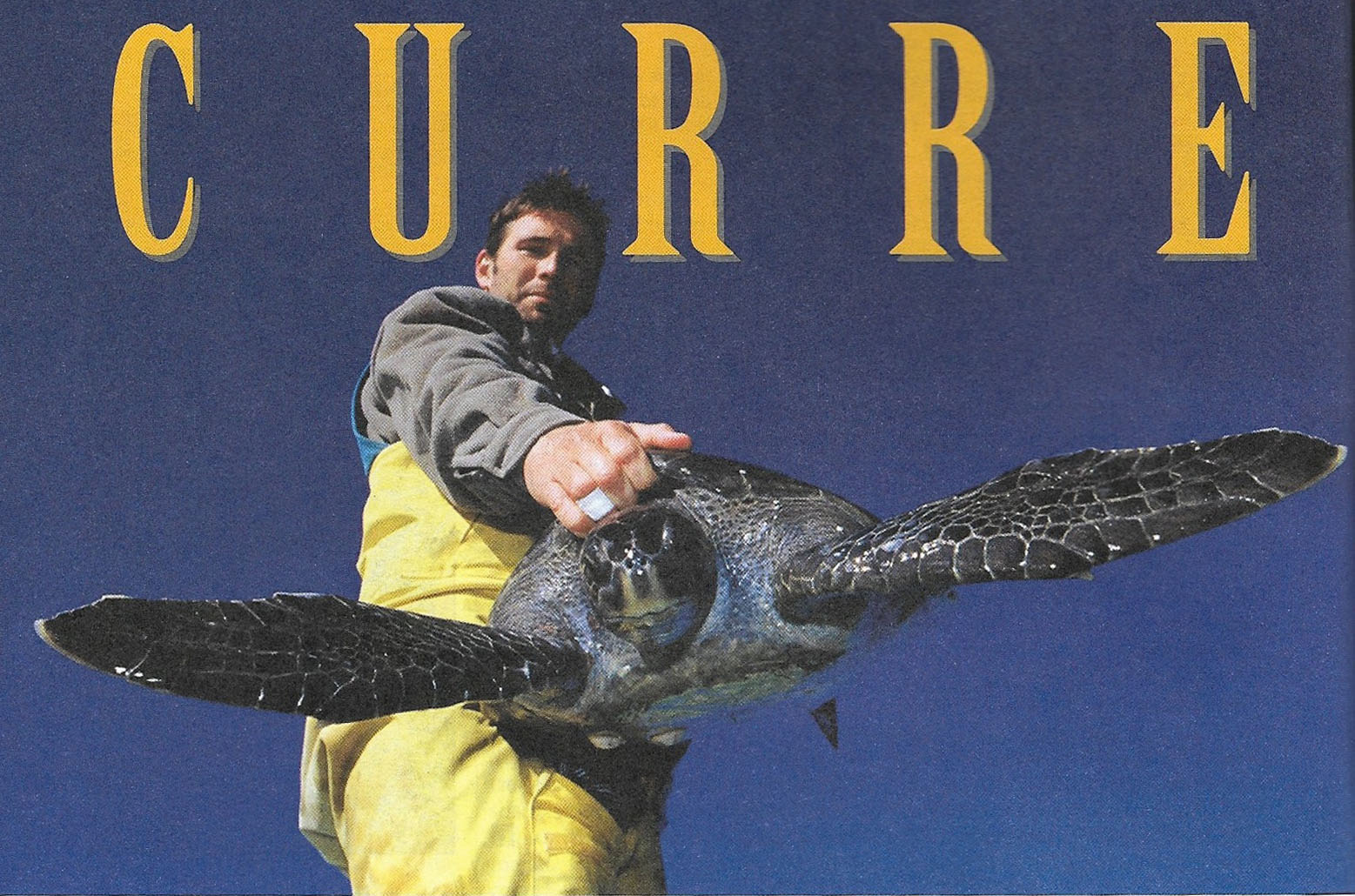

Groupo Tortuguero continues its David-vs.-Goliath efforts to co-opt fishermen and volunteers from Baja's fishing communities to monitor, tag and protect sea turtles. The group has dozens of sites along the peninsula and all have drug issues, ranging from trafficking to addiction. "I've interacted with fishers who were not 'poachers,' but were poaching for money to feed their habit," says Nichols.

During his two decades of fieldwork, he has learned to move around Baja's more "narco-saturated communities," peopled by crack addicts and used by drug dealers as safe harbors along trafficking routes. Volunteer manpower is too sparse to patrol all the turtle nesting areas 24/7, and fieldwork remains risky. Protection from law enforcement, while improving, has been marginal. Police are either corrupt or hesitant to enforce turtle laws for fear of run-ins with murderous drug lords who prowl land and sea.

But there have been recent gains. WiLDCOAST, a small conservation organization also co-founded by Nichols, has implemented a media campaign. It started in 2005, when Argentine singer and Playboy Dorismar attracted controversial attention by appearing in television and poster PSAs, hitting Mexican men- who eat turtle eggs mistakenly believing they are aphrodisiacs-below the belt. The message above a salacious Dorismar reads: "My man doesn't need to eat turtle eggs; because he knows they don't make him more potent." The bold campaign reached a global audiesnce of 300 million and resulted in a decrease in consumption of sea turtle eggs.

In 2006, World Cup soccer idols Jorge "El Brody" Campos and Kikin Fonseca joined WiLDCOAST's latest "Don't eat turtles!" campaign. And more recently, Baja's governor Narcisco Agundez publicly announced he does not eat turtle. He now promotes turtle watching over turtle eating, an unprecedented move in Mexico, where powerful people eat illegal seafood as a status symbol.

Meanwhile, "it looks like the (sea turtle) numbers are slowly coming up," says Nichols. "And if this continues, then it's possible to save the sea turtles. And they can become the symbol of a success story-that a grassroots movement can in fact protect a piece of the ocean. That's very powerful"

CONTACTS: Groupo Tortuguero, www.groupotortuguero.org: WiLDCOAST, (619)423-8665, www.wildcoast.net.

-C.J. Bahnsen

Client

E MAGAZINE

Date

May/June 2007