Study Helps Uncover Occurrence and Prognostic Significance of Cytogenetic Evolution in Patients with Multiple Myeloma

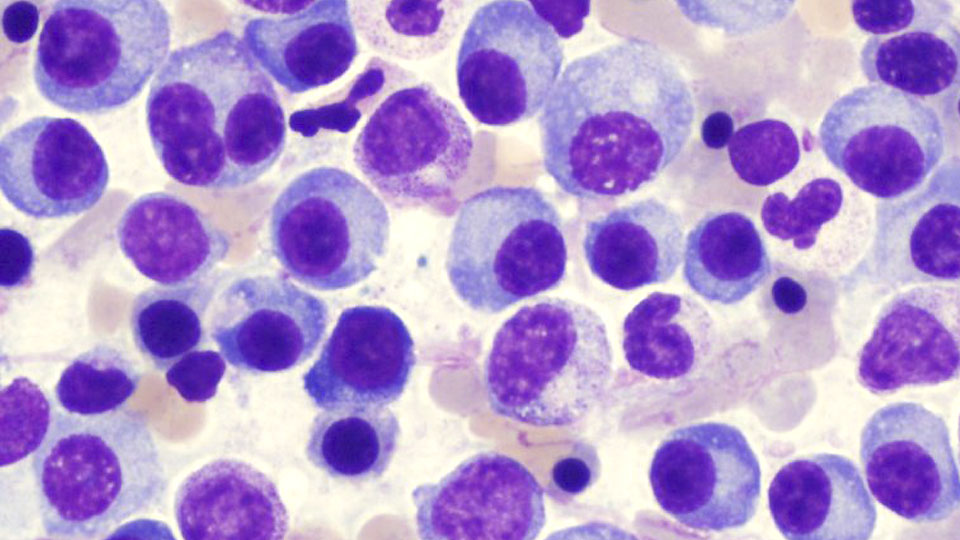

Multiple myeloma, a treatable but incurable disease where collections of abnormal plasma cells accumulate in the bone marrow, is the second most common type of blood cancer in the U.S. Cytogenetic evaluation at the time of diagnosis—which analyzes plasma cells from the bone marrow for abnormalities in the genes—has been shown to be of prognostic significance and is essential for risk stratification in multiple myeloma. However, little has been known about the development of cytogenetic abnormalities later on in the course of the disease or how this might influence prognosis.

Findings of a long-term study at Mayo Clinic, recently published in Blood Cancer Journal, suggest that the disease changes over time in some patients and not so much in others.

“There are several distinct genetic abnormalities that have been found to correlate with more aggressive disease,” says Moritz Binder, M.D., resident physician at Mayo and first author on the study paper. “Our study investigated how these abnormalities change over time and whether or not they still tell us something about the outlook of our patients, which is why we looked at repeated bone marrow examinations in these patients.”

The study cohort included 989 patients diagnosed with multiple myeloma at Mayo Clinic Rochester (between 2004–2012), including 304 with at least two cytogenetic evaluations. Typical gene abnormalities consisted of deletions or additional copies of certain chromosomes, as well as translocations—when a portion of a chromosome moves to a new position on the same or another chromosome.

Examining a patient’s bone marrow at the time of diagnosis is considered standard of care in the U.S. However, Mayo developed further refinements to identify certain subgroups of patients.

“By looking at the patients’ bone marrow at the time of diagnosis, we were able to identify certain abnormalities that make it more or less likely to develop new abnormalities during the course of disease,” says Dr. Binder. “Furthermore, the outlook for patients seems to depend not only on the abnormalities seen at the time of diagnosis but also on the ones that develop later on. This may be helpful information for doctors deciding whether or not a patient may need more intensive treatment later on in the course of disease.”

In the patients with repeated cytogenetic evaluations, the presence of t(11;14) at the time of diagnosis was associated with decreased odds of new cytogenetic abnormalities during follow-up, while the presence of at least one trisomy or tetrasomy (additional copies of chromosomes) was associated with increased odds of new abnormalities during follow-up.

The development of additional abnormalities during the three years following diagnosis was associated with increased subsequent mortality, adjusting for sex, age, the presence of high-risk abnormalities, and the number of abnormalities at the time of diagnosis.

Study findings suggest more favorable outcomes may be a marker of increased cytogenetic stability in this patient population. In other words, those patients who did not develop new abnormalities over time seemed to fare better.

One plausible explanation?

“Myeloma cells that are less prone to develop genetic changes over time may be less likely to develop resistance to treatment,” says Dr. Binder.

Although multiple myeloma remains incurable, use of novel drugs and risk-adapted treatment strategies have led to an increase in patient response rates. The median overall survival has almost doubled in the last 20 years or so, and more than half of the patients with unfavorable cytogenetics were alive three years after diagnosis.

“The landscape of myeloma is constantly changing with several new drugs being approved in the last year alone,” says Dr. Binder. “For example, therapy with bortezomib was found to be beneficial for patients with the specific abnormality t(4;14) at the time of diagnosis.

“Given the availability of a number of drugs that can be used later on in the course of disease, this data may be helpful, while acknowledging that this was one of the first studies looking at these changes over time,” Dr. Binder adds. “A lot of work has to be done before we will be able to make specific treatment recommendations based on these findings.”

Client

Mayo Clinic - Mayo Medical Laboratories

Date

6 June 2016