Human Cell Therapy Laboratory: Developing Drugs from the Patient, for the Patient

It’s almost a crime the outside world doesn’t know about the human clinical trials occurring at Mayo Clinic’s Human Cell Therapy Laboratory (HCTL) in Rochester. Currently, there are eleven (phase I) trials underway (or just finishing), investigating the use of cellular therapies. Developed in HCTL, these therapies are designed to treat chronic wounds—particularly patients with anal fistulas secondary to Crohn’s disease—renal stenosis, and fatal neurological diseases such as amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and multiple-system atrophy (MSA).

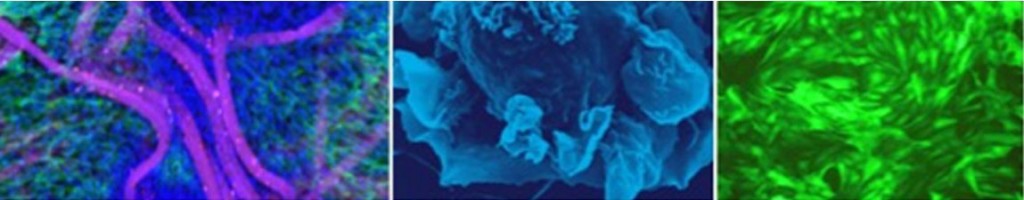

All of these trials are using autologous (derived from the patient’s own stem cells and delivered back to the patient) cell therapies. The stem cells originate from adipose (fat), bone marrow, or umbilical cord blood. Hence, rather than something synthetic and pharmaceutically manufactured, the stem cells act as “a drug from the patient, for the patient,” says Allan Dietz, Ph.D., biochemist and Director of HCTL. “We’re really driven by the fact that there are a lot of unmet patient needs out there, and lots of indications where [pharmaceutical] drugs have either continually failed or the whole patient need has been abandoned by the pharmaceutical industry. We need to come up with something else. So that’s the foundation we work off of, based in transfusion medicine.”

HCTL’s cancer vaccine platforms—currently focused on boosting the immune system against non-Hodgkin lymphoma and ovarian and brain cancers—are also showing promise in human trials. The vaccine process involves taking autologous monocytes from a patient’s blood and converting them into active, potent, mature dendritic cells. These cells “flip on a switch that really cranks up your immune system,” says Dr. Dietz. “We started this work on immune-based cancer therapies over fifteen years ago. I think the greatest change that’s occurred is that you can now affect the patient’s tumor by working on the patient—not the tumor. And I think it’s going to change how we treat cancer. It’s cheap, feasible, and extremely safe. It’s early, but we’re seeing very good evidence of improvement in cancer patients’ immune systems and evidence of long-term stable disease.”

The Human Cell Therapy Laboratory maximizes its efficiency by trying to identify broadly applicable platforms that have the most impact on the highest number of diseases. Another factor that amps up efficiency is its “one-stop shop” approach: The laboratory provides both the platforms and the research that goes into each one. It provides regulatory advice to physicians, helping to design the clinical trial and move things quickly through the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. It manufactures cells and, in some cases, helps monitor patient outcomes, performing some of the ancillary studies that happen during those trials.

Efficiency is of utmost importance because by the time patients enter a trial, they are in the eleventh hour of their disease or condition, having no other treatment options, which is why close, long-term collaborations between HCTL and Mayo physicians are paramount.

“We have really excellent, dedicated physicians who are not satisfied with what they can offer their patients,” says Dr. Dietz. “These are the men and women who are driven to provide something different for their patients. It makes us very efficient because we combine our expertise and develop the kind of teamwork that’s needed to move these cell therapies into the clinic as fast as possible. I have no way to prove it, but I think I have the best team at Mayo, period.

“We try and stay ahead of everybody by constantly improving on cell-based therapies. As our team collaborators move through phase I of trials, it becomes clearer to them how to modify these platforms for the next generation of trials. Then it comes back to our lab to work on those modifications to specialize a platform into something specific to those patient indications.”

Dr. Dietz likens his team’s work to providing Mayo physicians with a “toolbox.” And physicians who use these platform tools are beginning to combine them in innovative ways. In doing so, they’re bringing new options to the clinic. “We have one trial in which the measles virus—which is being used as an exciting technology here at the clinic—is being used to infect stem cells that home in on the tumor and deliver the measles virus to ovarian cancer,” says Dr. Dietz. “So you don’t get a measles virus/stem cell combination unless you have both tools in the toolbox.”

Meanwhile, HCTL continues to innovate cell matrix combinations, such as the recellularization of whole organs for transplant—with a goal of being the first to transplant a fully functional, recellularized liver in a human.

All of this begs the question: How soon will human cell therapies alter the practice of medicine as we know it?

“Cell-based therapies are already in the clinic now, with bone marrow transplant, for example. That’s still the foundation of our work,” say Dr. Dietz. “But I think we’re going to see these therapies creep into different parts of medicine at different rates, depending on how quickly we can demonstrate their usefulness. There will be places where it will be implemented relatively quickly, as with wound healing, because the cells seem to have a very unique and powerful capacity to heal wounds. I think in the next ten years, you’re going to be really stunned at some of the applications as cells find their place in therapy. I think it’s the next big phase of medicine.”

Client

Mayo Clinic - Mayo Medical Laboratories

Date

24 July 2015